Architectures of Jozef Jankovič

autorské motívy

Architectures of Jozef Jankovič

autorské motívy

Jozef Jankovič (1937 – 2017) devoted his work to the medium of graphics since the 1960s. He tried out various techniques and experimental motives, which challenged the borders of the graphics artform. In his Architectures and Projects series, Jankovič combined the atmosphere of totalitarian utopia with the aesthetics resembling virtual reality, pointing at the state of society with his specific humour.

Jozef Jankovič was among the most promising and talented Slovak sculptors in the 1960s, and he gradually gained recognition also in the European context. His artworks focused on human figures, deformed by social and political pressure, ideology and manipulation. Jankovič depicted a modern man, deformed and imprisoned in the course of history. However, with the start of Normalization period, he was pushed out of the official art scene. His large sculptural realisations – a group of statues entitled Victims’ Warning for the Memorial to the Slovak National Uprising in Banská Bystrica and the fountain in Bratislava neighbourhood of called Pošeň were removed. He was expelled from the Slovak Union of Visual Artists in 1972. Consequently, his works were not allowed to be legally exhibited either in Slovakia or abroad, and galleries were forbidden to purchase his works into state collections. His opportunities for architectural realisations, which represented Jankovič’s main source of income at that time, were also limited.

As a result of these changes, Jankovič turned his interest to smaller formats, such as jewellery and paper. Those included considerable cartographic works (for example the humorous series Czechoslovakia I. and II.), graphics in which he used found materials (e.g. a large Arabic cycle inspired by the patterns of Islamic architecture and ornaments), or a combination of typography and human shapes (the Journals cycle). Jankovič also explored the potential of computer graphics in collaboration with a mathematician Imrich Bertók. At first, he used this method for his experiments with geometric transformations, randomly generated values and programme errors. He later applied computer algorithms also for the creation of concepts for other graphics techniques and monumental sculptural realisations.

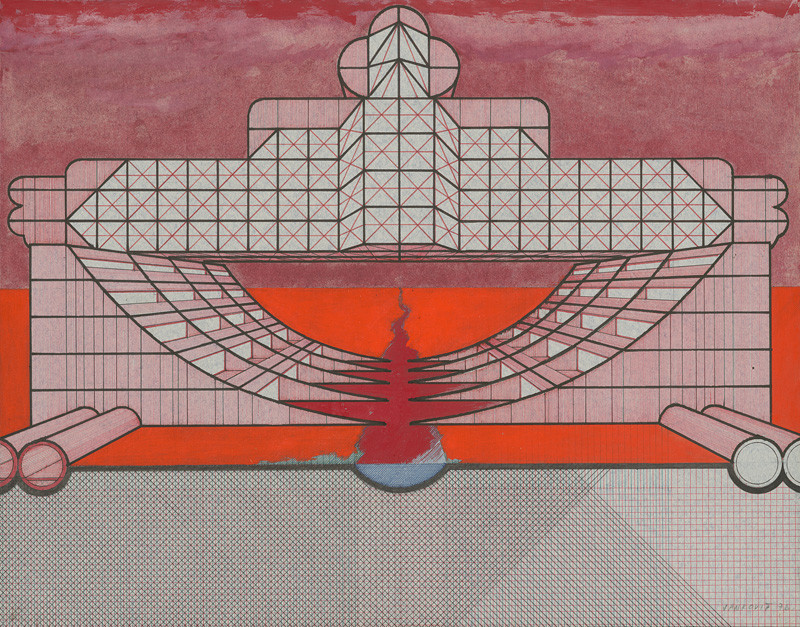

Jozef Jankovič – Project of a Parliament with an Inflatable Roof, 1977

Jankovič ironically baptised his art activities in the 1970s as „substitutive strategies“. Compared to existential motives of his previous sculptural works (which reflected fear, uncertainty, pain or lack of freedom), Jankovič's art was more sarcastic and ironical during the Normalization. Though, it still expressed a direct criticism of a tragicomic social situation and spectacular ambitions of the socialist regime. Because Jankovič was forbidden to construct his art works in a real space, he created designs for fictional and symbolic spaces. Some of them were meant for manipulation of human beings (interrogation, re-education, psychological bullying, etc.), while others used human figure and gestures on a monumental scale.

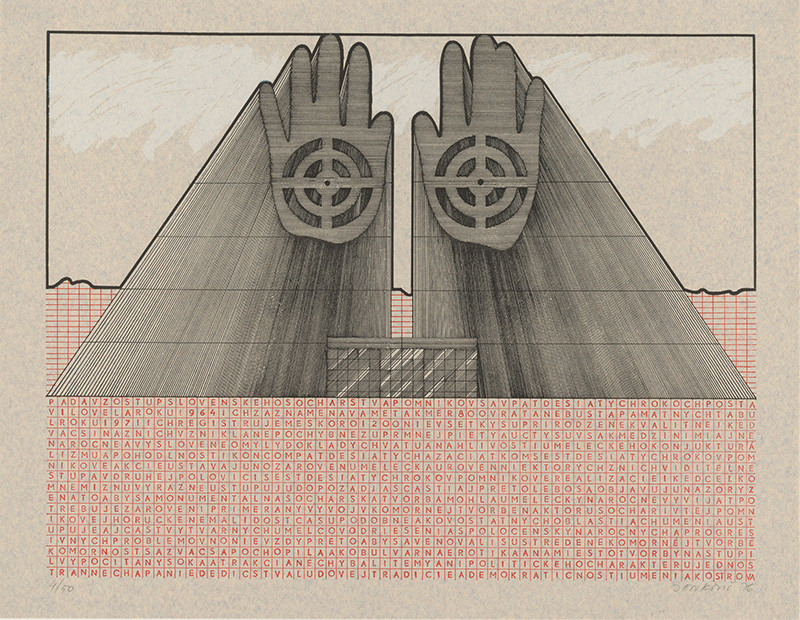

Graphical albums Architectures (1976 – 1978) and Projects (1977) contain a series of designs of fictional buildings that cross the boundaries between sculpture and architecture. Gigantic anthropomorphic monuments and buildings with bizarre functions present very expressive sculptures. At the same time, they manage to overcome the decorative function of sculpture in the public space, to which it is often limited. It is not possible to construct these buildings in reality, but that is not their ambition – they rather point to an extreme idea that architecture and urbanism should have an educative function. They serve as a paraphrase and parody of the utopian designs of French revolutionary architects, Russian constructivists, ancient monuments (The Colossus of Rhodes, the Sphinx) as well as the conceptual architectures of Austrian postmodernist Hans Hollein. Hollein was in favour of spreading the principles of architecture into all aspects of life and complete control of man over his environment. Jankovič's fictitious projects show a grotesque, Socialist Realism consequence of such ideas.

Jozef Jankovič – Architectures III. The Monument of Slovak Sculpture, 1976

The graphics and drawings in this series were created by a combination of offset printing, acrylic, india ink and clip art. Jankovič used the possibilities of computer graphics –

rhythmic repetition of lines, precise phasing of forms – as a basis for further work and colour composition. Jankovič drew most of the exact, machine-like and detailed designs actually by hand. He redrew computer-generated drawings from drawing plotter and combined fragments into larger units. The result very often resembled a virtual environment of a modelling programme. Some designs incorporate text fragments, for example, an extract from the issue of the Pravda daily newspaper.

The works in his collection contain several themes and interpretations. In addition to the obvious hints to totalitarian megalomania and mass construction, Jankovič also developed his theme of the annihilation of the human body. Buildings often resemble giant characters stuck in a concrete or stone, helplessly frozen in time and space and symbolising the spiritual stagnation of that time. The proportional system of architect Le Corbusier says a man is "a measure of all things". Jankovič aims, on the other hand, to "convert a human figure to the measures of architecture". This shift of meaning had a special dehumanising effect. It refers to the mechanisation of human existence, the substitution of a living artist by something artificial and the disappearance of a human principle from architecture. The worrying symbiosis of a man and his creation – architecture, encourages us to reflect on the ignorance of spectacular construction projects that have the ambition to transform (humanise) natural landscape and to adapt people's thinking to their perception.

Jozef Jankovič – Project of a Communist's Party Hotel on the Moon, 1976

Jankovič alternates these concepts with his unique humour. The combination of outspoken satirical titles together with absurd measures and function of his buildings add somehow lighter perspective to the utopian (sometimes even post-apocalyptic) atmosphere of the works. The Portable Pneumatic Agitprop Centre, intended for propaganda aims, resembles a head of a jellyfish with its tentacles and a shrieking mouth. Communist’s Party Hotel on the Moon, The House with Eyes Blinders or The Villa of an Unknown Politician Secured against a Nuclear Attack indicate the paranoia and separation of the political elite from the reality. The shape of a human head defines the projects of the representative sculpture and painting studio, The Villa of a National Artist as well as the Radio Journalists’ Club. They show the ideal notion of a conforming cultural agent and his pompous and mentally empty cage. The Memorial of the Slovak Sculpture looks like a magnificent tribute, but in reality, it evokes a human being just before his execution.

The Slovak National Eros Centre connected with the People’s Observatory has a phallic shape and separate entrances for people from different regions – Detva, Liptov, Záhorie, Kysuce, Košice, etc. Erotic hints can also be found on the proposal of The Most Modern Factory for Preservatives or on the Regional Office of Public Security. The housing estate project contains multi-layered towers in the shape of human figures, gradually forming to indefinable geometric shapes. The Cultural House for a Municipality of 5.000 inhabitants has a rough cubic shape and a „spartakian” figure on the roof with a cube instead of a head. Those individual buildings have certain utilitarian blindness in common – they predominantly focus on purpose and effect, regardless of taste, humility or common sense. Their precise work and a certain futuristic charm look like they want to warn us that their attractive look and grandiosity can be deceitful.

Jozef Jankovič - Project of the House with Eye Blinders, 1984

The introduction of the Architectures’ album contains a commentary by Jiří Valoch, analysing the form, motives and the wider ideological context of those works. You can read it using a picture zooming function. You can also order printed reproductions of the works from the Slovak National Gallery collection.

"... each realistically thinking artist must bear in mind that he has to make more statues, drawings and paintings than the unfavourable environment is capable of destroying. If you don’t do this, you have no right to complain." – Jozef Jankovič in an interview for the book Slovak Ateliers

Sources:

- Diana Majdáková - Digitálny obraz v slovenskom výtvarnom umení 20.storočia. Uplatnenie počítačovej grafiky a digitálnych technológií v tvorbe statického obrazu. Diplomová práca, Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave, Filozofická fakulta, 2008

- Ivan Jančár, Juraj Mojžíš - Jozef Jankovič : Plynutie času = Flow of time, Galéria mesta Bratislavy, 2016

- Juraj Mojžiš - Jozef Jankovič : 1957 - 2007, Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum, 2007

- Zora Rusinová, Aurel Hrabušický, Katarína Bajcurová - Jozef Jankovič : Tvorba z rokov 1958 - 1997, Slovenská národná galéria, 1997

- Katarína Bajcurová - Jozef Jankovič : Retrospektíva 1960-2003, Mistral Art, 2003

- Katarína Bajcurová, Aurel Hrabušický, Katarína Müllerová - Slovenský obraz (anti-obraz) : 20. storočie v slovenskom výtvarnom umení, Slovenská národná galéria, 2008

- Denisa Gura Doričová, Daniel Brunovský - Slovenské ateliéry, 2010